17 years ago, shortly after we acquired Breg, I consulted a local builder about some renovation projects I had in mind. His advice:

“You must crush!”

“You will always have problems with this house. You must crush and build new!”.

Though his prophecy of problems did come to pass, I had, of course, no intention of ever ‘crushing’ the house. My vision was to restore and preserve it. And after years of renovating little by little, the time had come for the big one: replacing the roof with what was the original material: wooden shingles.

Do the Koroški Shake

I say shingles – but strictly speaking – I’m talking about shakes. Shingles are sawn whereas shakes are split along the grain giving them a rough surface, a more natural look and a longer life. I will however use the terms shake and shingle interchangeably for this article.

I knew that the roof had originally been a sole layer of wooden shakes, because they were still in place, visible from inside the building when we’d first bought it. However, they had long since been covered over with corrugated felt sheets – normally only seen fit for dog kennels and hen houses – presumably because the previous owner wanted a quick, cheap fix.

Seventeen winters had since taken their toll on that quick, cheap fix, and now, many of the felt sheets were torn and sagging. Indeed, a few years back, a leak had sprung. I’d clambered onto the roof and replaced part of the ridge material, buying myself a little more time, but I knew the weatherproof capabilities of the felt were degrading, and that every winter, I risked a more catastrophic failure.

Slovenian shingles: easier dreamed than done

My dream had always been to one day re-shingle the house with wood. But that was easier dreamed than done. There was a certain ‘Koroškan shingle style’ I’d seen on houses and barns in the region; the same style that was still visible under the felt sheets. This style is – in my opinion – the most beautiful of all wood shingle types. Using very long ,very thin shingles which overlap in a certain pattern – it creates a very appealing aesthetic, which also happens to be the traditional style for this region.

So, around five years ago, I started to make enquiries. If I saw a beautiful shingle roof whilst driving around some Koroškan backroad, I would stop, knock on the door, and ask who had carried out the work. I also invited two different shingle roofers from other parts of Slovenia to quote, but in the end, the type of shingles they offered was not what I was looking for.

The years passed and while my corrugated-felt roof sagged further, my quest to find a local willing to do the job was not going well. I eventually began to question the entire wisdom of choosing wood shingles at all; despite their beauty, shingles are invariably more expensive and shorter-lived than metal or tile roofs.

After much heartache, I reluctantly shelved my long-held vision and began investigating modern materials instead. But though I could buy tiles or metal sheeting easily, finding a roofer to actually come and assess the job was almost impossible. My calls to builders went completely unanswered. No one seemed interested in the job.

The only guy I managed to coax up to the house – a friend of a local friend – never replied to my calls or messages after his first and only visit. I later found out that he thought the job was too complicated and he had plenty of other work on. Not that he ever bothered to tell me that himself.

Time was running out. With each winter that passed, I worried that water was getting in. But with no roofers lined up, I considered doing the job myself. I visited a local building merchant, but they strongly advised me to get a professional to first assess the roof and the weight it could bear before selecting my materials. I was back to square one.

It was in the midst of this dearth of willing roofers that the idea of wood shingles resurfaced once again. After all, I knew the building had been originally designed and built for shingles. That meant no problems with overweight terracotta tiles and no worries about moisture barriers or condensation traps that might come with a metal roof. And a beautiful shingle roof was what I’d always dreamed of; the cherry – well, spruce as it turned out – on the top. It felt like the Slovenian Gods were telling me to forget modern materials and restore the original wood roof.

The art of shingle-making: a dying craft

So I once again began to search for someone who could and would make a shingle roof, but this time, closer to home. The craft of shingle making is dying. Even in Slovenia – where wood shingle roofs are not uncommon – they are nowhere near as prolific as they once were. And so finding those who can still wield a froe is not easy.

But through a Slovenian friend – Miha – I finally managed to get a lead: Jože – a man who still made and laid shingles. Now, understand that Jože does not advertise his shingle services. He doesn’t have a website or a brochure. You won’t find him anywhere on the internet. If you don’t have a connection to him, there is no way ‘in’.

It was a bright day in early summer when Miha and I drove off into the wilds of Koroška – winding up a rounded mountain road through pasture and forest – to reach Jože’s farm. He appeared from his house, dressed in a white apron stained with blood. We’d caught him in the middle of koline – the annual farm ritual where pigs and cows are slaughtered, sawn up, sliced up, minced up and transformed into salami, steaks and sausages.

He invited us in and put shot glasses of schnapps in front of us. As Jože drew on a cigarette, I noted he had striking, different-coloured eyes – one brown, one green – and an ageless appearance. I could not tell if he was a well-cured forty-something or a youthful-looking sixty-something.

Speaking in my crude Slovene, with Miha translating the more complex topics, I began to feel out the man. Amongst his entrepreneurial farming activities, Jože counted bread baker, sausage maker, cider brewer, schnapps cooker, and – of most interest to me – shingle shaping and roofing.

I quickly discovered Jože had cheek and charm; a sense of humour that I immediately warmed to. By the time the effects of the second schnapps had hit, I was sure he was the man for the job.

“I can help out with the work,” I offered.

“Well, then I’ll have to charge you more!” he replied.

We did not immediately settle upon a deal, but some weeks later, after further negotiations on the price per square meter, an agreement was reached.

A lesson in making traditional Slovenian shingles

Six months later, ever intrigued to learn about Slovenia’s crafts, I visited Jože’s farm on a crisp winter’s day to witness the process of shingle-making. He led me into a heated enclave of a large wooden barn set high on the hillside.

He pointed out large sections of spruce he’d just cut from his forest. At first, I was surprised to learn that spruce – a fast-growing conifer, not known for its durability – was the shingle wood of choice. But he assured me these shingles would have a long life – and indeed – many of the houses I’d seen in the Koroškan style had used spruce. He told me that felling the trees in winter also added to their life span and that the straight grain meant they could be riven into very long (>1m), very thin shingles (<1cm) which dry very quickly after rain, thus making them last several decades on a roof.

He demonstrated how each section of spruce was quartered, how he scraped off the bark using a hoe-like tool, and how the heartwood was removed. Next, Jože used something called a froe to bevel the edge of the wood. I asked why – and if I understood him correctly (he spoke in a heavy Koroškan dialect) – it was purely for aesthetic reasons.

Last came the splitting or ‘riving’ as it’s known. Using the froe and a mallet, Jože carefully began to split each section of the log into very long, very thin shingles. All winter, he would work away in his barn to stockpile tens of thousands. And after being dipped in a copper-based preservative these would eventually end up on the roofs of a few lucky local houses, creating beautiful, traditional roofs.

It was very satisfying to know that each spruce shingle had come from a tree not far away and been shaped by Jože’s hand. Seeing the man in shingle-making mode was the final piece of the picture I needed to confirm he was the right man for the job.

Returning to his kitchen table, our agreement was cemented by a shot of schnapps and a handshake. No contract was signed; no deposit paid. I would put my faith in Jože, and he would trust I would cough up when the job was done.

Shake it up: the wood shingles go on

Spring appeared and I was keen to get the job moving. Jože assured me I was ‘in the queue’ but was unable to give me a specific month, let alone a date. After a few false starts, by the end of summer, my turn had come. An added complication of the access road being blocked for weeks by loggers worried me but Jože found another way up through the forest and arrived with a trailer load of shingles – one of many he would have to haul over the two-week period.

I was both intrigued and anxious as he began to prise off the old felt roof. I had no idea what condition I might find the underlying roof structure in. I feared rot and decay so was pleasantly surprised to find that not only were the timbers sound, but the original wood shingles – which must be at least 50 years old – beneath the felt were largely in good shape.

“If it rains now – it would be fine,” said Jože, referring to their intact condition.

They would remain in place, and we would replace the felt sheets with the new shingles on top.

It would take 7000 shingles to cover the roof. They were laid in a way that looked haphazard to my untrained eye but I came to see there was a very specific pattern. Each shingle is slightly tapered, both along its length and along its width, adding further complexity to how they should be arranged. There were almost always three layers and were angled carefully with the thin edges directed a certain way.

It had been a hot, late summer with temperatures around 30c, and up on the roof – even hotter. I was amazed that Jože spent so long up there only pausing to come down for a cigarette and more shingles. In fact, Jože seemed to get his entire nutritional intake from tobacco smoke. He barely consumed anything else though I noted he never smoked whilst on the roof.

He worked his way along the ridge, only removing the old covering in sections so there was never much uncovered roof exposed. I was impressed by how few tools Jože worked with; just a ladder, hammer, pry bar and a hell of a lot of nails. Aside from a small chainsaw, which he only used occasionally, Jože didn’t use any power tools at all. And apart from his son who came along to help one morning, and me who adopted the role of groundsman for a couple of days, unloading the shingles and passing up a stack now and again – Jože completed the entire job alone.

I think at first Jože was not entirely overjoyed to have me around. I know that having the ‘client’ watching over you is never fun, and he’d already told me that he didn’t need any help. But I left him to it, sporadically offering coffee, Laško beer, and helping out where I could, without breathing down his neck.

He seemed to warm to my presence eventually. One day he had to leave early; it was bake day and he and his wife had to prepare a large batch that they delivered to local towns and villages. The following day, he kindly brought me half a round loaf. It was truly some of the most delicious bread I’d tasted and I told him as much.

The following day he brought me another half loaf and half a stick of homemade salami. It was an entirely different interaction to your average building contractor. Indeed, Jože is not really a builder. He’s a craftsman who chooses to continue the now very scarce art of shingle making because he loves it.

It was extremely rewarding to see Breg finally getting its traditional roof back. For too long it had been topped in an ugly (though to be fair, weatherproof) hat – but to see one of the last Koroška shingle craftsmen at work had been a rare pleasure.

I hope this roof will see me out, though depending on how long both it and I last, that may not be the case. Estimates of spruce shingle lifespans range from 30-40 years, depending on weather conditions. It’s possible that by the time it needs replacing again, there won’t be anyone left who still has the skill to make it.

There’s a part of me that daydreamed about becoming Jože’s apprentice and learning the art of shingle making and laying myself. If he’d ever allow me, maybe one day I will, but I got the feeling that when it comes to making Koroški shingles – Jože is a lone wolf.

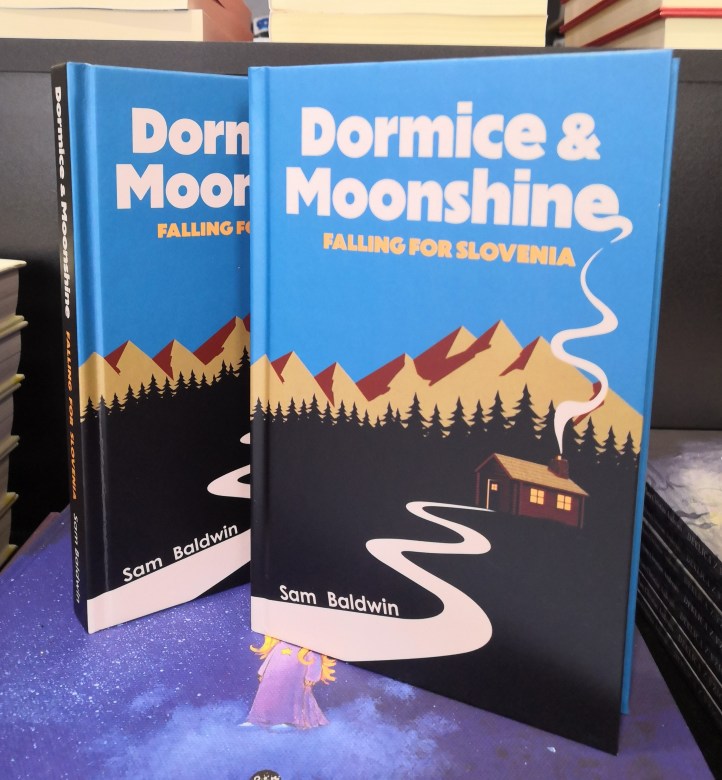

If you’d like to read more about my adventures living and working in Slovenia – you can read my book: Dormice & Moonshine: Falling for Slovenia – available now from all Amazon stores.

Thank you for bringing into life this almost lost shake making tradition. And congrats on your new roof, it looks beautiful. As does the whole Breg house. You are doing a great job renovating it!